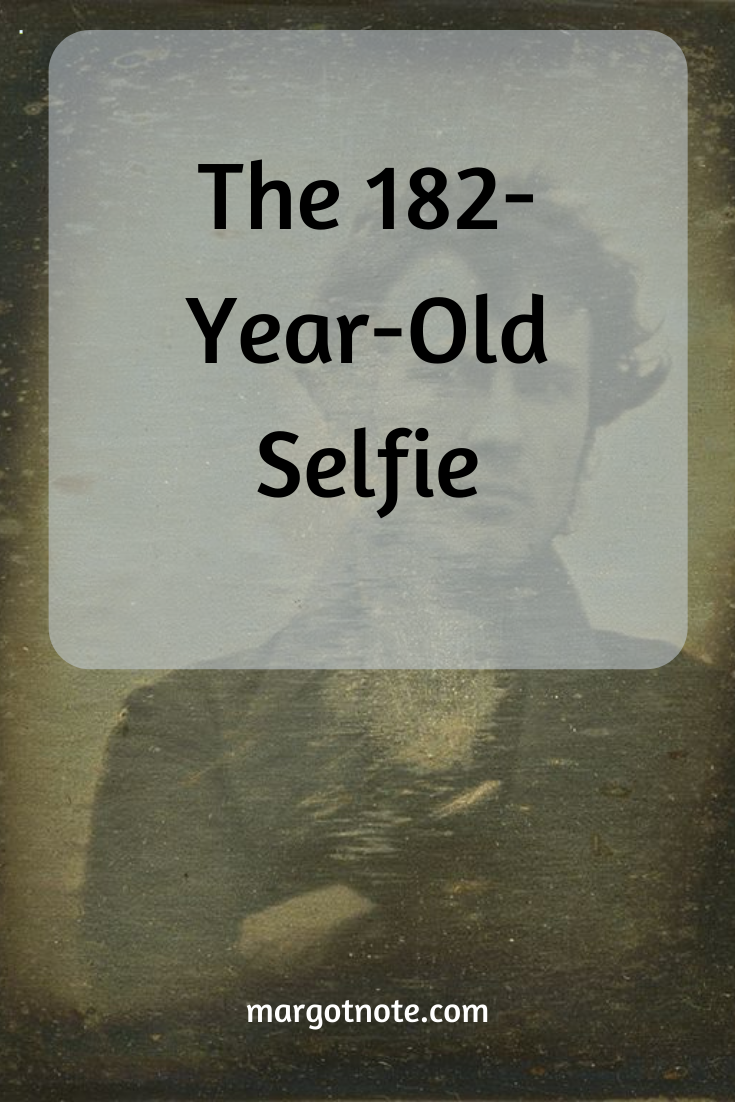

In October 1839, a thirty-year-old Philadelphian named Robert Cornelius stepped into the rear lot of his family’s lamp and chandelier store. The bright sunlight necessary for his experiment saturated the yard. He placed a camera, crafted from a tin box fitted with an opera glass, on a support. Inside was a solid silver plate made light sensitive with iodine. He removed the lens cover and stood as his eyes watered from the sun. After five minutes of stillness, he replaced the cap. Later, he performed a series of chemical processes, including exposure to mercury vapor, to develop the plate and reveal a picture of himself.

His portrait displays a man with crossed arms and tousled hair, eyeing the camera warily. Cornelius’s vibrant depiction belied the long exposure required to make it, and his commanding presence and the off-center composition produced a compelling image. Recognizing his achievement and wanting to capture the moment, he gazed into the lens towards his audience. He imagined himself as one of them – the first ever to see his own photographic visage. One hundred and eighty-two years after its production, the image still captivates us. The daguerreotype now resides at the Library of Congress, with Cornelius’s handwritten note on the back describing it as “the first light Picture ever taken, 1839.” Cornelius’s likeness is the world’s original selfie.

Cornelius, Robert. Self-portrait. 1839. Photograph. Lib. of Cong., Washington D.C. Lib. of Cong. Web. Accessed October 22, 2020. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004664436/.

A selfie, or a self-portrait taken by a cell phone camera and distributed through social media, is a new word for an old phenomenon. Artists have practiced self-portraiture for centuries, and the selfie as an artistic expression dates back to the origins of photography. Additionally, sharing photographic self-portraits is nothing new. The popularity of inexpensive, paper-based cartes de visite in the 1860s, the creation of photo booths in the 1880s, and the invention of Kodak’s Brownie camera in 1900 enabled casual, tradable portraiture and the self-creation of identity. While selfie activity has escalated in recent years, we have only invented a term for the time-honored experience of exploring our ipseity.

After Daguerre announced the invention of his photographic process in August 1839, American photographers soon surpassed the quality of their French counterparts, partly because Philadelphia was one of the leading scientific cities of the world. In the fall of that year, Joseph Saxton approached Cornelius for the silver-coated copper plates required for his daguerreotype experiments, and Cornelius adapted his metallurgy and chemistry knowledge from his father’s lighting business to photography.

With the aid of chemist Paul Beck Goddard, Cornelius used bromide to reduce exposure times for daguerreotypes to less than a minute. As a result, he opened two of the earliest photographic studios in the United States. They operated until 1843, when the increased demand for domestic lighting fixtures monopolized his time. Though Cornelius’s photographic career was brief, thirty of his daguerreotypes have survived. Their quality, along with his portrait, has made him a luminary of early photographic history. He was instrumental in transforming photography from an experimental process into a commercially viable enterprise.

As with Cornelius’s image, initial self-taken digital photographs were flawed; capturing photographs without a viewfinder often created overexposed, out-of-focus, or off-center images. In 2010, a breakthrough occurred when the iPhone 4 featured a front-facing camera. Most devices now include these cameras so that users can take self-portraits while looking at the screen, optimizing framing and focus. The camera’s quality and resolution improves which each upgrade, and the average person can snap photos with no technical knowledge required. Instagram, launched in the same year, generates selfies with artful tones, replacing the harshly lit images of years past. Small, square images invite connections between photographers and viewers, and the app’s visual and textual confines make single subjects more legible than complex ones. Cornelius’s portrait, with his hipster-like appearance and lo-fi aesthetics, could easily pass for a contemporary selfie.

As selfies reached their cultural velocity recently, their detractors associated them with narcissism, exhibitionism, body image issues, and the male gaze gone viral. Rather than dismissing the trend as a derivative of digital culture or a millennial fad, selfies are a means to mark existence and to construct representations of the desired self. Selfie, with its diminutive -ie suffix, is an expression of endearment for the self and the related enterprises of documentation and identity. The appeal of selfies arises from their ease of production and distribution and the control they grant photographers in presenting a curated version of themselves to the world. Their snapshot aesthetic makes these constructed narratives seem more natural and spontaneous than they are; they offer a self-conscious authenticity.

One can only wonder what the message was that Cornelius wished to convey in his selfie. Perhaps he was showing his ingenuity and expertise in demonstrating that portraiture was indeed viable for photography. His second and final self-portrait was taken in 1843, the year he closed his studios. In this daguerreotype, Cornelius performs an experiment on a fabric-draped table used as an armrest for photographic clients. Unlike his first selfie, Cornelius’s face is obscured. The eyes that stared defiantly at us are now, one assumes, focused at his laboratory equipment. His hair, once disheveled, is neatly parted. Rather than skewed and blurred, the crisp image is centered on his work, which is the focus of this unique selfie. Cornelius wished to broadcast to the world that he is a scientific master, demonstrated in his vocation of lighting and avocation of photography.

Cornelius, Robert. Self-portrait. 1843. Photograph. George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

The polished surfaces of Cornelius’s daguerreotypes displayed their viewers like a looking glass. His first, a quarter plate measuring 3-1/8 by 4-1/8 inches, and his final, a 1/6 plate measuring 2-3/4 by x 3-1/4 inches, can rest in the hand, creating a closeness with their audience. Incidentally, the images are similar in size to smartphones, which are gazed into just as much as mirrors. Literally and conceptually, Cornelius’s selfies reflect back on us, demonstrating the universal desire to record ourselves for posterity.

As artifacts of human activity, photographic self-portraits expose the resonant, complex integrity of a person, which others can understand just by looking. To create a self-portrait is to try to understand how one is regarded and how one would wish to be perceived. It is a form of alchemy, once chemical, now technological, that changes our perception of the world and ourselves. Selfies, whether digital or daguerreotype, reveal the human desire to be seen and remembered.