The records that you generate and collect in the course of your life or business are of immediate value to you in conducting your day-to-day business. After activities end, related records serve as evidence of your activities. Maintaining records in a consistent, organized way helps preserve them and makes them accessible for future users. These records of enduring value are your archives.

Once you know some archival principles, you can adapt professional methods to your records. As a result, you can confidently sort through your treasures and discover the stories they hold. You can more comfortably make decisions about items worth preserving, and you can wisely invest the resources you have available for the project. You will be in charge of your history instead of the other way around.

If you'd like to learn more, continue reading this introduction to archives.

The Archival Mission

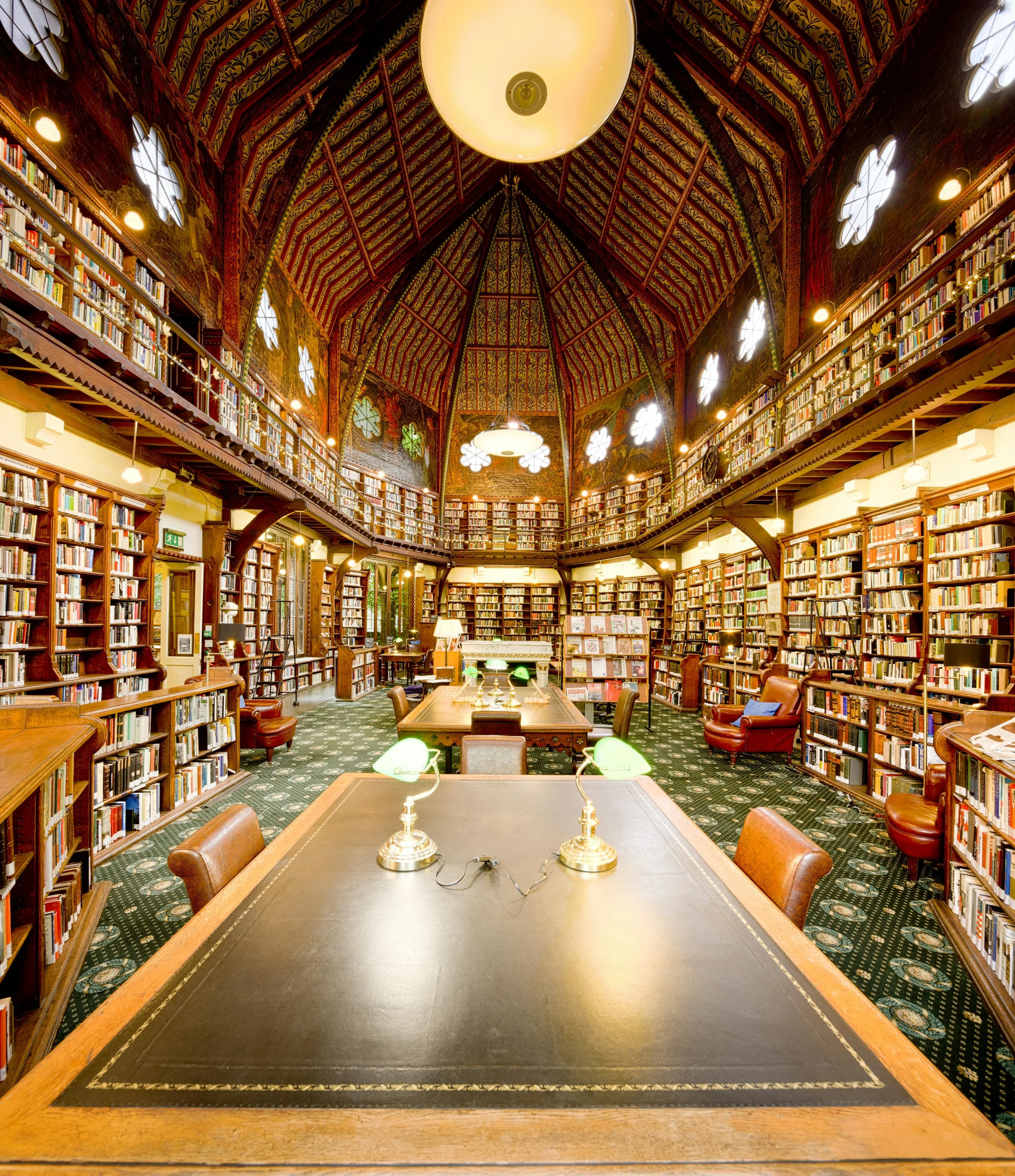

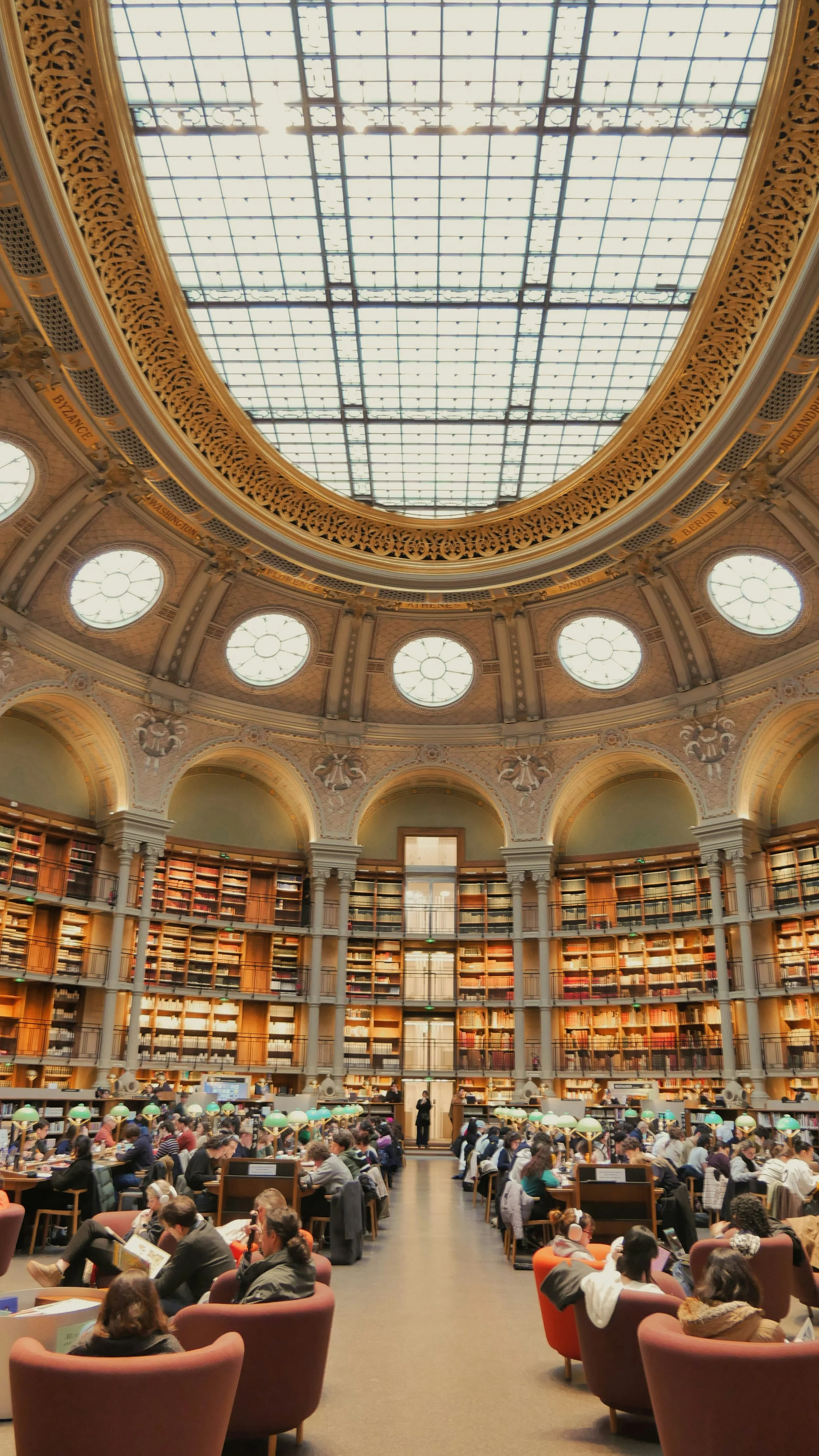

Archives have a mission to identify records of enduring value, to preserve them, and to make them available to patrons. For all their differences in size, scope, and staffing, repositories share a commonality: they are responsible for the collections entrusted to them for use by future researchers. By embracing the responsibility for communicating these activities through preservation, archivists ensure that the work done today is preserved for future generations.

What are the characteristics of archival materials?

Archives are usually original. There’s usually only one copy of each item, and it doesn’t exist anywhere else.

Archives document what people do in their daily lives. In other words, they initially began life as records.

Archives were not created with the public in mind, as published materials are. They weren’t made for any purpose beyond that of providing evidence of what the creator did or decided to do.

Archives have value even after their creator has finished with them. Archivists use the term enduring value to describe their worth.

Archives rely on context to give them meaning. Information about how an item was created is as important as the item itself.

Archives are kept for the long-term and usually forever.

Archives can be in any format, from handwritten letters and bound ledgers to photographs, sound recordings, and spreadsheets.

Why are archival materials saved? They can serve:

As long-term memory, providing access to history and knowledge

As a means to access the expertise of others

As instruments of legitimacy and accountability, facilitating social interaction and cohesion

As a source for understanding and identification of ourselves, our communities, and our society

As vehicles for communicating political, social, and cultural values

As evidence of continuing rights and obligations, such as a contract or marriage license

Want to learn more? The following posts will provide you with a better understanding of archival repositories:

How to Prepare for an Archives Visit

Why Digital Archives Expand Access and Awareness

Preserve, Curate, or Steward? Changing Definitions in Digital Preservation

Defining Archives

Archives are materials that an individual or organization accumulates over the course of a lifetime or while conducting business. An individual can collect personal items such as correspondence, journals, and home movies, or career-based materials such as speeches, manuscript drafts, and research files. Organizations produce these types of records, but can also include information relating to marketing, communications, legal issues, and finances.

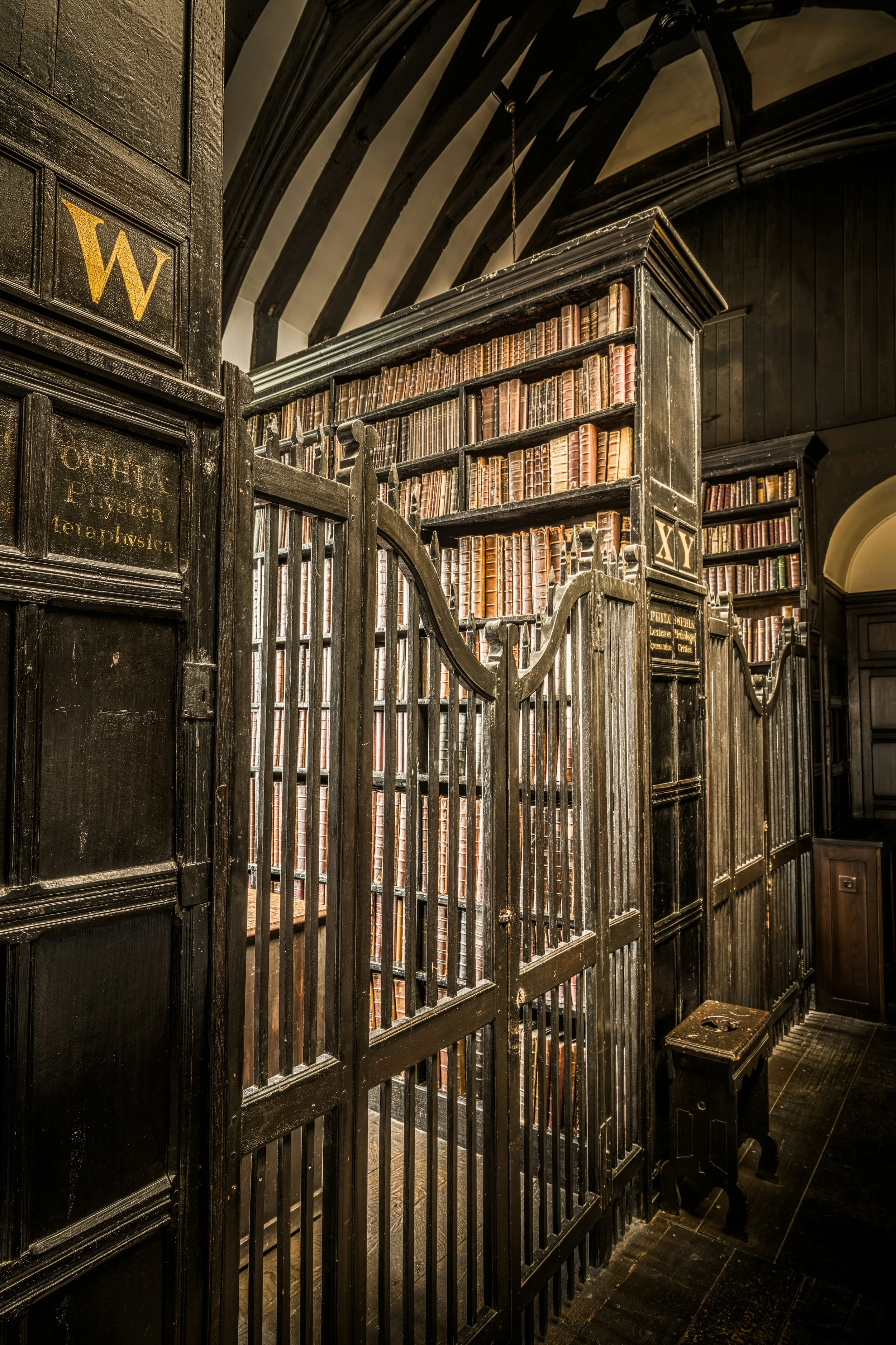

The term archives has three common meanings. The first denotes materials. Archives are composed of collections of unique records of invaluable importance. They can include letters, photographs, sound and visual recordings, and digital files. The second refers to an agency; the archives is the department or organization responsible for selecting the materials of enduring value, such as a university’s archives and manuscript division, or a historical society. The final meaning regards facilities. The archives is the building that holds and protects historical records.

Archives play a crucial part in documenting memory. Archival records serve as evidence of the many activities, relationships, transactions, decisions, goals, challenges, and achievements that occur daily. Archives not only preserve evidence of past activities but also of the social role the creator occupies in its local and global world. They allow users to interpret events because they are the closest things to unbiased evidence of what happened in the past.

If you'd like to explore more, check out these posts:

What Makes a Successful Archival Project?

Digital Preservation: A Community Effort

Maintaining Sustainable Archival Collections

The Role of Archivists

Have you ever wondered who safeguards our collective history?

Archivists do.

Archivists organize and protect permanent records and historically valuable documents. The repositories in which they work provide the materials with environmentally controlled, secure, physical and digital storage, and archivists oversee the proper handling and use of these records. They also make them available for research.

Archivists are professionals who are experts in managing a wide range of diverse historical materials, from ancient manuscripts to the latest in digital technology. Archivists are educated and trained to preserve, organize, and provide access to these materials so that our historical record is complete. They are also at the forefront of protecting digital content—creating strategies to adapt to ongoing changes in scale, technology, and standards.

Here are some posts about how archivists determine and lead archival projects:

Identifying Worthwhile Archival Projects

Characteristics of Effective Archival Project Managers

Developing Leadership Skills with Archival Projects

Analog, Digitized, and Born Digital

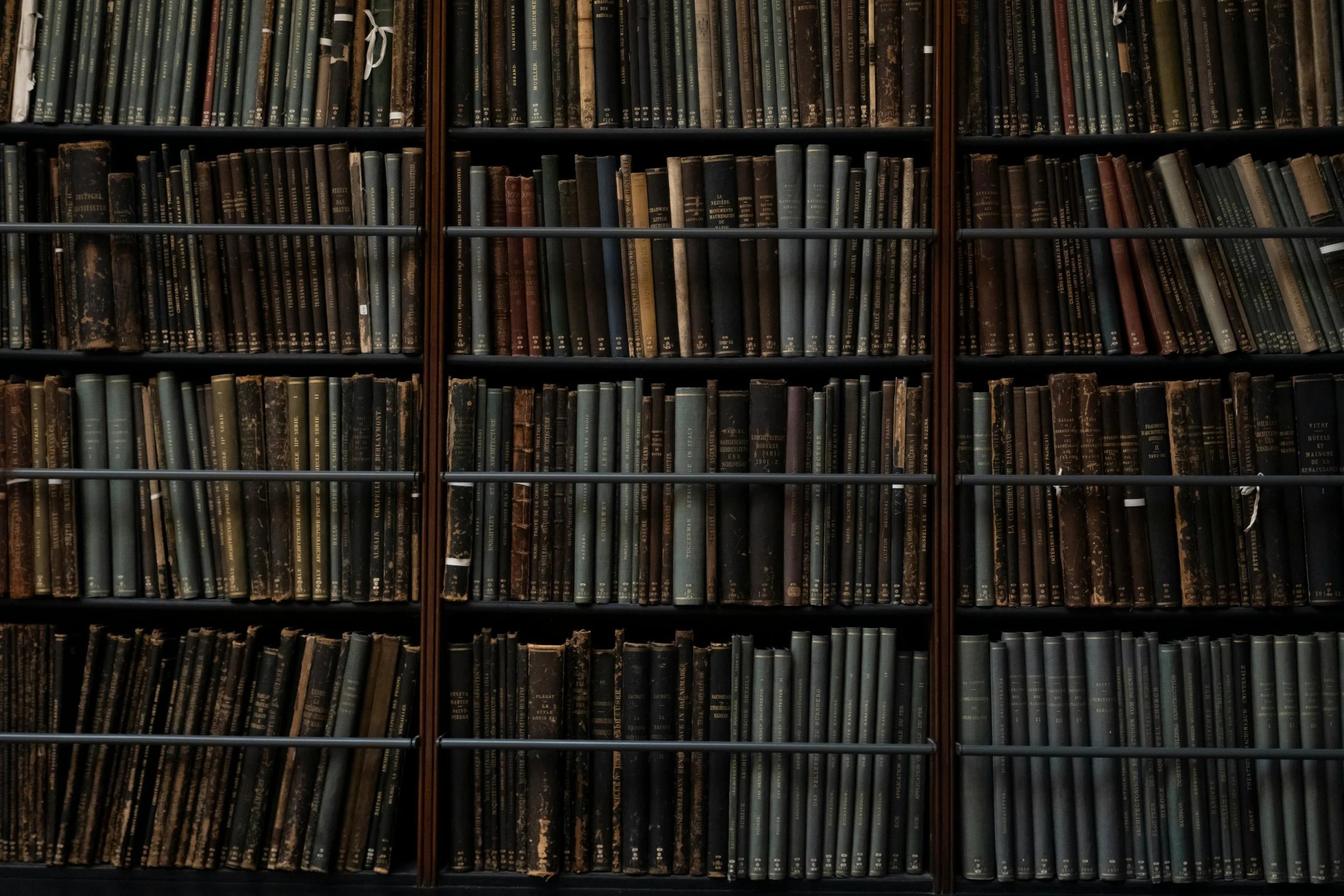

When people think of archives, they usually think of old, dusty items. That's certainly not true! I prefer to use the terms enduring value or continuing value rather than archival value because archival suggests something is old, and therefore, the value is in its age.

This idea is true with some documents, but not all. A record created on your computer today could have the same enduring value as a record created by hand 100 years ago.

In most organizations, records with enduring value are only about three to five percent of an organization's records created throughout its history. The same is true with records related to individuals.

Both archivists and the users of their collections are interested in the long-term preservation of archival materials as well as ensuring continuous access to them. Consequently, archivists are concerned with preserving both physical (also known as analog) and digital resources (including those that are digitized and those that are born digital and do not exist in analog form).

Digitized materials function as surrogates of analog materials. A digital scan of a Polaroid photograph and an MP3 audio file of a digitally reformatted cassette tape are examples of digitized versions of analog items. Items are born digital if they began life in digital form. A Word document, an email, and a photograph from a smartphone are examples of born-digital items.

Archival collections may consist of paper documents until a point in time, and then shift to a combination of analog and digital records before shifting entirely to computer-generated records, frequently with duplication between the record types.

Here's a trio of posts to explore further:

Three Fundamental Digital Preservation Strategies

Best Practices for Planning a Digitization Project

Selection for Digitization – Best Practices

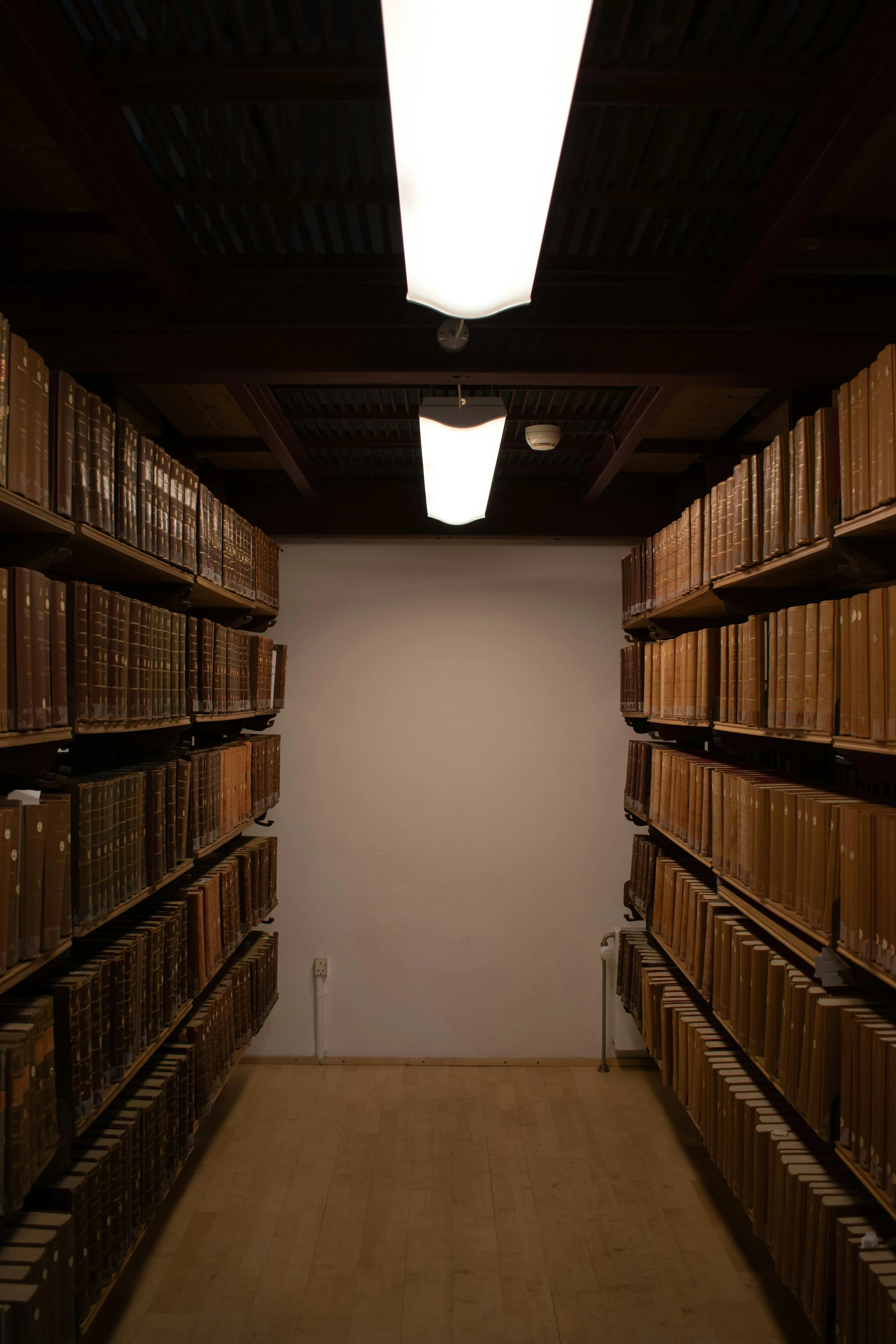

Acquisition

Because vast amounts of material are available for acquisition, archivists must define and justify what, how, and why they collect what they do. A collection development policy connects archival material to the overall mission and vision of the archives program while supporting other initiatives within the organization. A collection development policy states what it collects and, more importantly, what it does not. A strong policy also keeps the archives from becoming storage units for unwanted materials.

Remember yesterday's email when I said that only a small part of materials having enduring, continuing, and archival value? Well, even a smaller sliver of those records make it to an archival facility. Archivists ensure that materials with lasting importance are saved so we can explore—and learn from—our past.

Want to learn more? Check out these posts:

Writing a Collection Development Policy

Writing a Digital Preservation Policy

Accession Considerations for Photographs

Appraisal, Accessioning, and Deaccessioning

Evaluation and selection are part of the process of creating and maintaining archives. In the archives profession, these activities fall under the umbrella of archival appraisal. Appraisal is the means of determining whether records have enduring value and therefore should be retained. Appraisal decisions consider several factors, including the records’ provenance and content, authenticity, completeness, condition, and intrinsic value, among others. Appraisal, in this context, is distinguished from monetary appraisal, which estimates fiscal value.

Archival appraisal ensures that only significant records that represent a time, event, place, or decision by an individual, group, or community are kept. Appraisal keeps collections to a manageable size and ensures that archivists’ limited time and resources are not wasted on useless materials. Appraisal allows archivists to shift from the tunnel vision of examining each item individually to considering their records broadly.

Appraisal is also vital for digital files. Many people believe that everything digital should be preserved, especially because storage is cheap. However, the resources to support digital content, such as IT support, are expensive. Additionally, hardware, software, and storage media must be replaced periodically. Not all digital content warrants long-term preservation. Instead, archivists focus on identifying the content that does.

When an archival repository acquires collections, professional archivists accession records according to their collection development policy. When items are removed for destruction or transfer, they are deaccessioned. These archival processes consist of a sequence of formal activities, allowing careful consideration of every collection that enters or leaves an archives.

Read more about appraisal in these posts:

A Primer on Archival Appraisal Values

Choosing Which Digital Archives to Preserve

Reappraisal and Deaccessioning

Archival Principles

Archivists believe that some records ought to be preserved long-term, even after their immediate usefulness has passed—and the records should be maintained as wholly as possible, in their original order, with critical information about context and connections kept intact.

Maintaining materials from one creator together as a group is referred to as provenance. This principle dictates that while archivists create subject headings in their catalogs, they do not rearrange materials in topical configurations.

Another fundamental archival principle is original order. Original order preserves existing relationships and information that can be inferred from the records' context. It also uses the record creator's mechanisms to access the records. Rather than dictating an order, archivists try to find and maintain the order that already exists.

Archives are differentiated from libraries or museums because archivists organize materials in the aggregate, not as individual items. Whereas a cataloger would create a record for a book or a museum registrar for a painting, archivists organize historical documents by groups. The largest group is the collection for personal papers or record group for organizational records.

Series is the most common unit of archival groupings. A series is accumulated for a specific purpose, during a distinct period, and the records in a series usually are arranged in order. This group may include an apparent filing system arranged alphabetically, chronologically, numerically, topically, or some combination of these. It may be a grouping of records based on similar function, content, genre, or document type. Processing depends on establishing series for collections or uncovering the series that the creator used. A subseries is a body of items within a series that is distinguished from the whole by filing arrangement, type, form, or content.

Instead of the usual blog posts that end these emails, I'd like to direct you to one of my books, Creating Family Archives: A Step-by-Step Guide to Saving Your Memories for Future Generations. In the volume, I explain in detail the process of arranging and preserving your own personal and family archives. The audience for this book is non-archivists who want to learn the tips and tricks that professional archivists use in their work. I've also found that people enjoy giving this book as a gift to friends and family. I've certainly used it as a way to describe and explain the work that I do and the value of preserving records of enduring value.

Processing, Arrangement, and Description

Archivists ensure the future accessibility of their collections through processing. The term refers to the steps that are taken to prepare historical records for use. Processing is the core of archival work because it groups items, folders, and formats into similar units and then structures those units into meaningful relationships.

Archivists act as intermediaries between the creators of materials and the future users of the collections. With their expertise, archivists decide the best ways to provide access to an enormous quantity of records, sometimes consisting of hundreds of boxes in a single collection. Processing allows both archivists and researchers to understand the importance of each collection, what each collection contains, and where each item in the collection is located.

During processing, collections should be arranged first, then described. Arrangement and description are linked, as each depends on the other. Arrangement refers to what items are grouped and the order in which the groups are placed; it is related to the archival principles of provenance and original order. Description is the development of written information concerning archival materials, such as their content and context. Guides, called finding aids, explain collections in detail and are used to locate materials. Processing also includes some preservation activities, such as rehousing materials in archival enclosures.

At the end of processing, archivists will have both physical and intellectual control over their collections. Physical control is understanding various aspects of the collection, such as quantity and location. Intellectual control is gaining a degree of mastery over the scope or content of the records. In other words, physical control is knowing the “what and where” about the collections, and intellectual control is knowing what they contain.

Want to learn more? Check out these blog posts:

The Current State of Description for Archives